In his influential essay “The Storyteller,” Walter Benjamin says “There is nothing that commends a story to memory more effectively than that chaste compactness which precludes psychological analysis.” A story that resists the claims of the analytical mind allows for a deeper “process of assimilation” by the listener, such that it is “integrated into his own experience” and he will be more apt to repeat the story and pass it on — which is of course essential to the story’s survival.

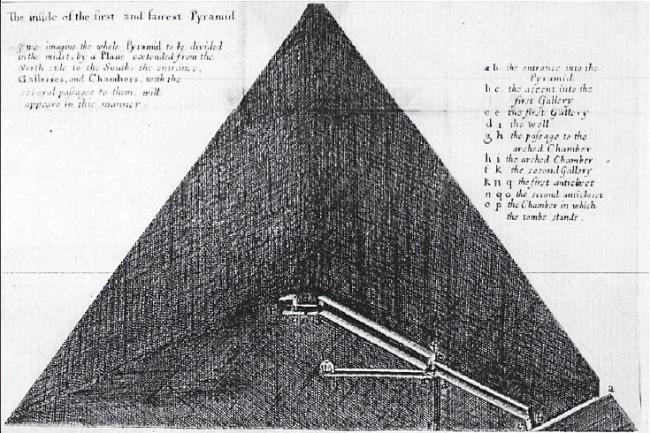

At first reading one might conclude that Benjamin is subtracting literature and storytelling from the cold grip of psychology, but he is actually describing a receptive state to verbal material that allows for the unconscious to go to work; after all, as Benjamin says, the “process of assimilation” is something “which takes place in depth” and in “a state of relaxation,” more specifically “mental  relaxation.” It is specifically the preserving and passing on of stories that interests Benjamin here, analysis can always come later. Story and storage, then, are intimately linked: a story “preserves and concentrates its strength and is capable of releasing it even after a long time”– like dormant seeds, Benjamin says, locked up in a pyramid and still retaining their “germinative power.”

relaxation.” It is specifically the preserving and passing on of stories that interests Benjamin here, analysis can always come later. Story and storage, then, are intimately linked: a story “preserves and concentrates its strength and is capable of releasing it even after a long time”– like dormant seeds, Benjamin says, locked up in a pyramid and still retaining their “germinative power.”

Gertrude Stein, a master of the striking vignette, provides a fine example of Benjamin’s “chaste compactness” in her memoir Paris France:

There was a girl in a café who was very fond of a dog who used to come there regularly with a

man and she regularly gave him a lump of sugar, one day the man came in without the dog and said the dog was dead. The girl had the lump of sugar in her hand and when she heard the dog was dead tears came to her eyes and she ate the lump of sugar (Paris France, Liveright, 1970, p. 34).

Interestingly, Stein’s vignette resembles a joke; all it needs is a three-part structure and a clearer punch line. But of course it isn’t, and this illustrates a vital distinction: whereas a joke, as Freud says, catches the unconscious off guard and momentarily releases pent-up tensions, a story such as Benjamin describes will release its secrets much more slowly, if ever.

Stein’s vignette seems to suggest a moral, but if there is one, that moral remains latent and ambiguous. Why does the girl eat the sugar? To ease her sorrow? To take the place of the dead dog? Or out of mere mechanical habit, life going on in spite of all? We can’t know. The “and” in Stein’s phrase “and she ate the lump of sugar” seems a particularly fine instance of Benjamin’s narrative subtlety and restraint, as it coordinates the sentence without elucidating any motives. So the story charms us, rather than conveying any certain meaning, and among the story’s charms is the perfect contrast between the salt of the girl’s tears and the sugar crystals we imagine melting in her mouth. But isn’t it appropriate that sugar be bitter, if one considers for a second that French sugar is the product of colonial sweat and toil, and the legacy, like the pyramids, of a brutal history of slavery and social death?

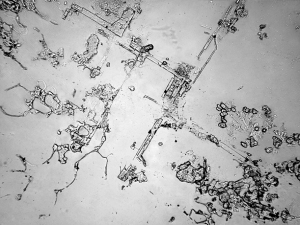

Tears, then, stored away in perpetuity. I was reflecting on Stein’s instance of frozen and ambiguous mourning when I came across a recent story in the Smithsonian about Rose-Lynn Fisher’s photographs of tears under a microscope. Fisher’s project “The Topography of Tears” was born in a period of sadness and loss, and the artist used some of her own tears as subject matter, discovering remarkable abstract crystalline patterns she likened to aerial photographs of geological terrain. “Eventually,” she says, “I started wondering—would a tear of grief look any different than a tear of joy? And how would they compare to, say, an onion tear?”

Scientists tell us there are three categories of tears: the basal, which functions to lubricate the eye, the reflex, which responds to an environmental irritant, and the psychic. With respect to the latter, the Smithsonian helpfully informs us that “because the structures seen under the microscope are largely crystallized salt, the circumstances under which the tear dries can lead to radically dissimilar shapes and formations, so two psychic tears with the exact same chemical makeup can look very different up close.”

Or, as Benjamin might say, the pictures of tears display a “chaste compactness which precludes … analysis.”